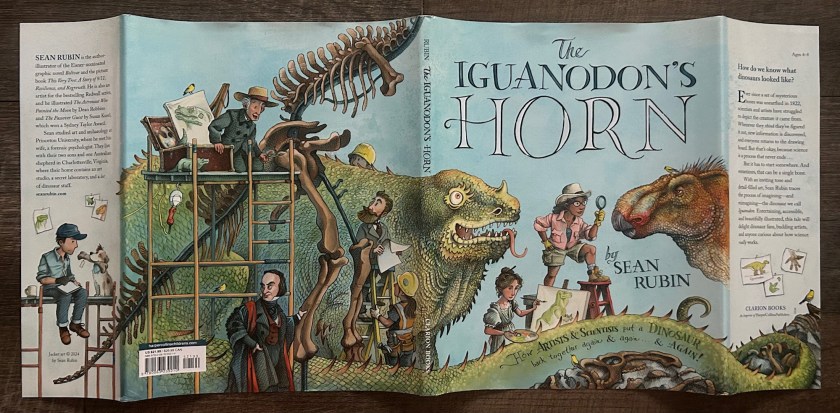

Some of my favorite books are those that examine the history of paleontology, and our changing perspectives on what exactly the prehistoric world looked like. Sean Rubin’s The Iguanodon’s Horn makes for an excellent example of exactly that, following the development of the field through the lens of how people depicted one of the first dinosaurs ever described: Iguanodon.

Rubin discusses the history of Iguanodon in the context of five rough “eras”, defined at least partially by the paleoart of the time. This is its chief difference from the conceptually similar retrospective book, The Tyrannosaur’s Feathers, which “corrected” aspects of a retro Tyrannosaurus piece-by-piece, but not necessarily in a historical manner. Even more so than The Bone Wars, Rubin lovingly recreates all the classic paleoart referenced, even when poking a bit of fun at their expense.

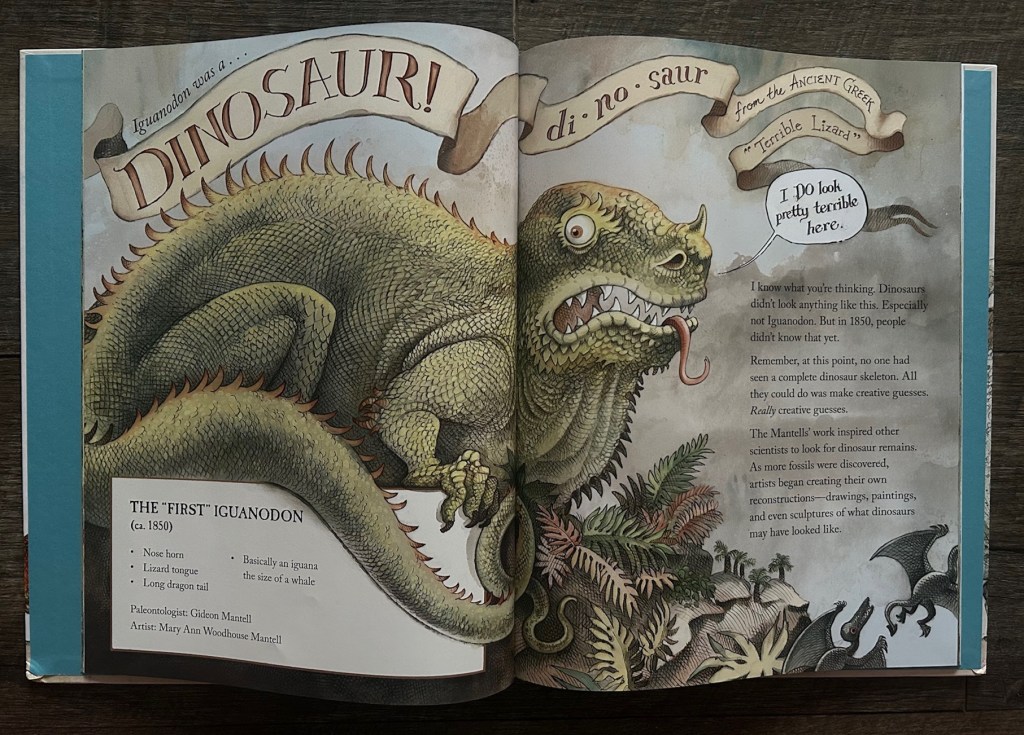

The main body of the book begins with the initial discovery of Iguanodon by Gideon and Mary Ann Mantell. I like that Rubin emphasizes Mary Ann’s contributions to the research and reconstruction, as historical notes indicate that she had more to do with all that than is often appreciated.

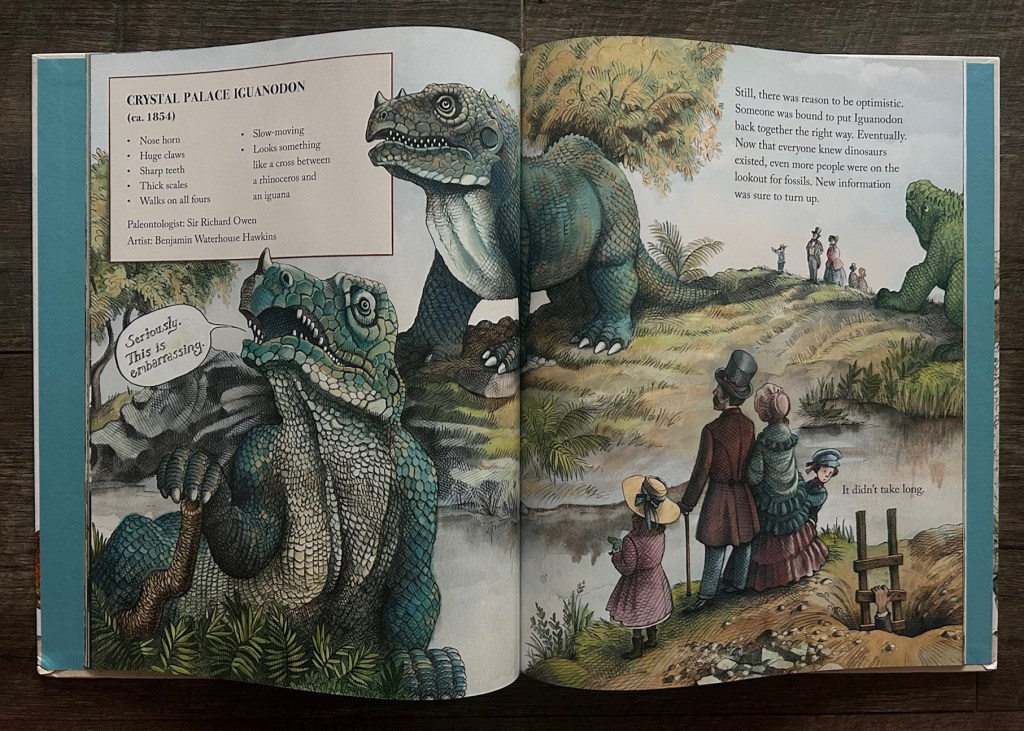

Given that I’ve already covered most of the historical information relevant to the second “era” with my reviews of The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins and The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, I won’t dwell too much on this section other than to complement Rubin’s recreation of the Crystal Palace models.

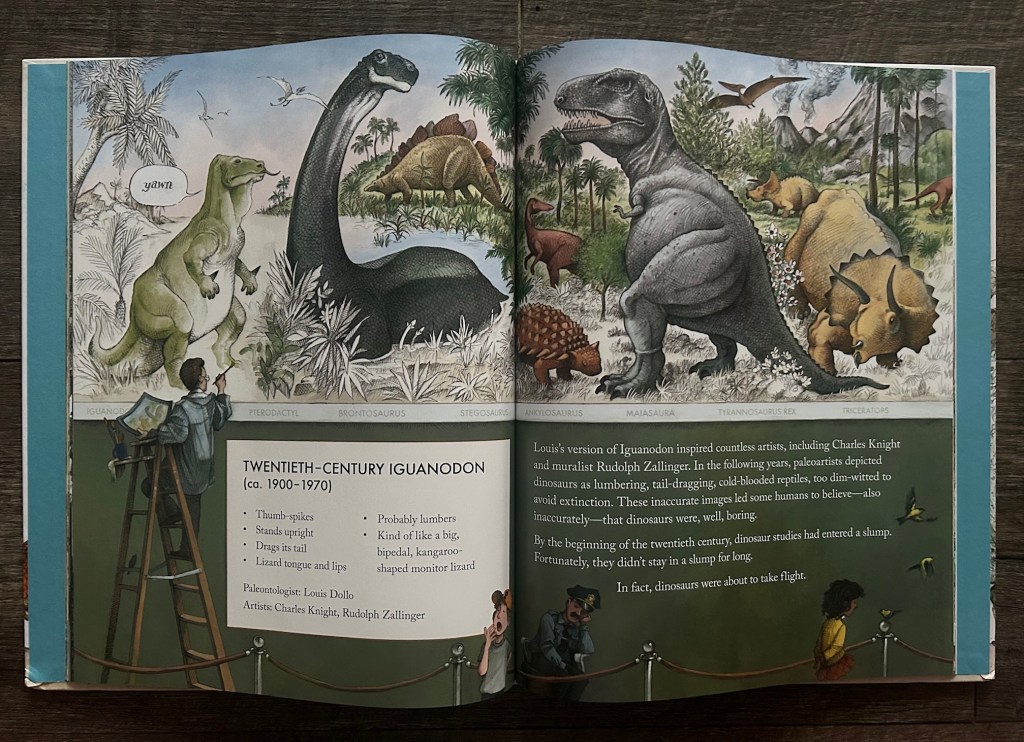

I haven’t had much of a chance to discuss the type of paleoart characteristic of what Rubin defines as his third era, so it’s nice to be able to look at some of it here. I’ve heard of the story of the Iguanodon herd in a coal mine before, but I’m not sure I’ve seen it represented artistically in this way before! The serendipitous nature of the find complements how revolutionary Louis Dollo’s subsequent reconstructions feel in contrast to what came before it, even if, as the book describes it, dinosaur science entered a slump during the latter part of this era. I rather like the fantasy mural that blends aspects of several artists from this time period, from Zallinger’s T. rex, to Knight’s Brontosaurus, to Neave Parker’s Iguanodon.

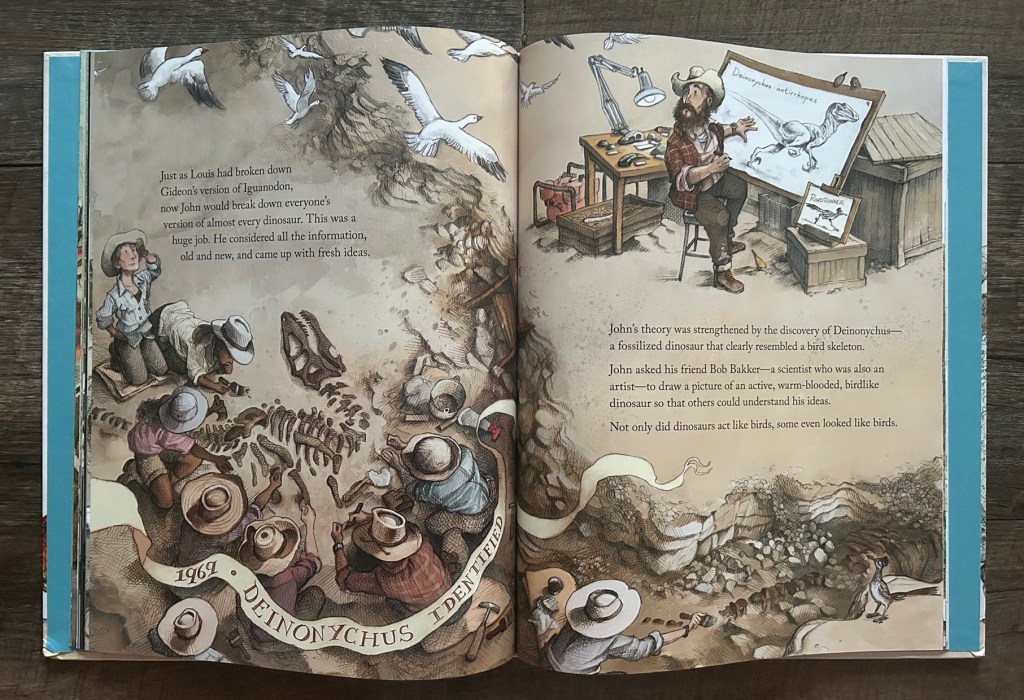

The Dinosaur Renaissance detours away from Iguanodon just a bit, as the discovery of Deinonychus was the real driver of change in this fourth era, though Rubin still of course demonstrates the impact this had on the book’s star. (The meta-illustration of Bob Bakker at work illustrating Deinonychus is a particularly nice touch.)

EDIT: Marc Vincent has since published his own review of “The Iguanodon’s Horn” at Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs, and I think he makes a good point about this section’s de-emphasis on Iguanodon being largely the result of apparent U.S.-centrism rather than an inevitable shift in perspective. An emphasis on the work David Norman rather than Ostrom & Bakker might have been preferable here in order to keep the focus on Iguanodon. As long as I’m editing this to include other people’s perspectives, I’ll also note that several people voiced concerns that the various comments made by the various Iguanodons regarding their own appearance felt more like disparaging the work of older paleoartists, rather than my inclination to see it as poking a bit bit of gentle fun. I can see how this might teach impressionable audiences to look down on the serious work that went into previous reconstructions, so I figured it was important to note that here.

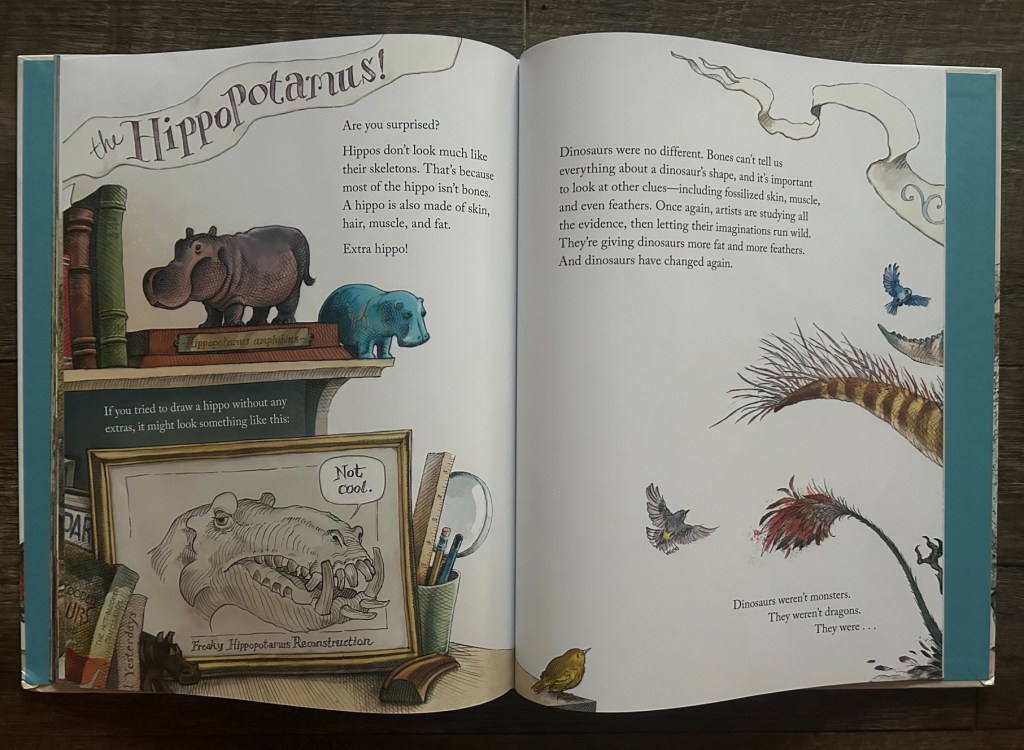

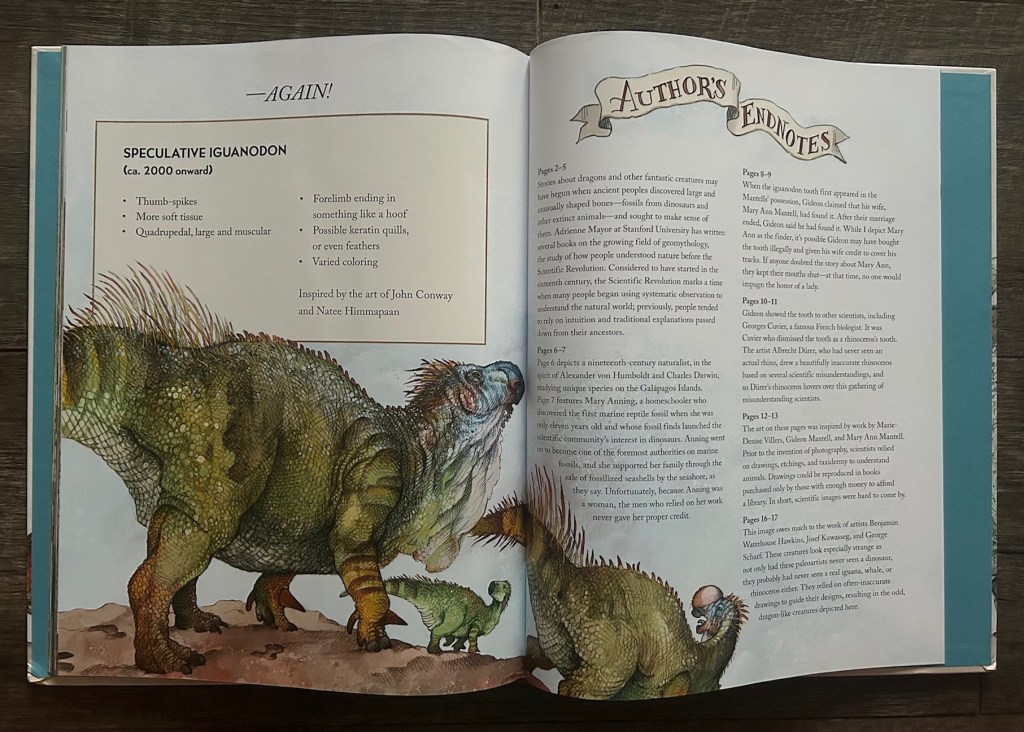

The final section leans hard on All Yesterdays as a major catalyst behind some of the current trends in dinosaur science (which some call the “Dinosaur Enlightenment”, as a followup to the “Renaissance”). We even get a couple of direct references to the book, most obviously with the hypothetical “how paleontologists might reconstruct a hippo” example that goes viral on social media every so often. (More subtly, the fan-tailed Leaellynasaura from All Yesterdays also makes an appearance, next to other dinosaurs more generally inspired by the movement generated by the book.) Taking the relevant scientific and artistic suggestions to heart, Rubin really sells the bulky, fleshy Iguanodon with plenty of visual flare.

The author’s endnotes provide extra information and historic context for everything presented throughout the book, including notes on the inspirations behind certain reconstructions that may have not been mentioned in the main text. I was pleased to see John Conway and Natee Himmapaan mentioned in particular, as I think they both deserve wider recognition (and not just because I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with both of them in person at TetZooCon!). I highly recommend The Iguanodon’s Horn. It’s generally comparable to Boy, Were We Wrong About Dinosaurs!, but rather higher quality in terms of both information and illustrations. While not as broad in its historical scope as Dinosaurs, Fossils and Feathers, I think the tighter focus is to this book’s benefit. Limiting the scope to a single dinosaur species, especially one so long-studied as Iguanodon, really helps emphasize how the science has changed over time. The Iguanodon’s Horn thus more than earns the Dino Dad Stomp of Approval, and I hope to see it influence future generations for years to come!

3 comments